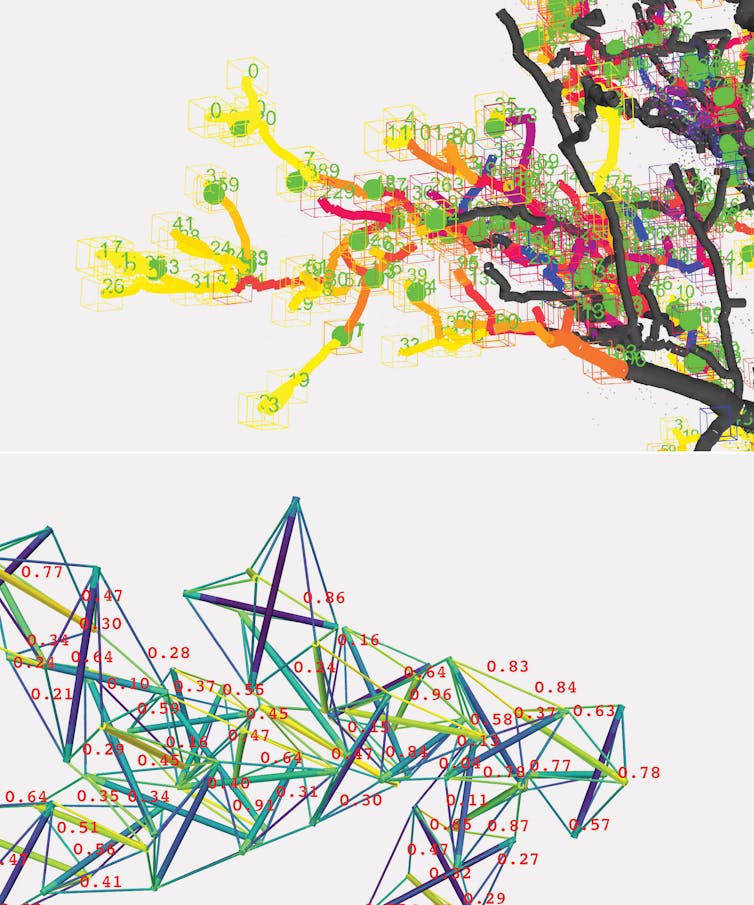

In the vast, beautiful landscape of Tasmania, the mountain ash, the world’s tallest flowering plant, stands as a living testament to nature’s ingenuity. These remarkable trees, capable of reaching over 100 meters and living for centuries, are not just silent giants; they are crucial components of their ecosystems. Yet, despite their vital role, their numbers are dwindling due to human activity, highlighting a profound disconnect between our world and the natural one. At the Deep Design Lab, we believe that humans consistently undervalue plants and the powerful lessons they offer. Our research into Tasmania’s ancient eucalypts has revealed a wealth of wisdom for urban planners, designers, and the public. By learning from nature’s brilliant solutions, we can create more resilient, biodiverse, and sustainable living environments.

The Power of Dead Wood

In the pursuit of tidy, controlled spaces, humans often remove dead trees and fallen branches, viewing them as a hazard or an eyesore. However, this practice strips ecosystems of a vital resource. Dead wood provides essential habitat for a vast array of wildlife, including microbes, insects, lizards, birds, and mammals. These species often prefer dead trees to living ones because the wood is easier to digest and the leafless branches are more accessible for perching and observation.

Beyond their ecological role, diverse ecosystems also support human health and wellbeing. Designing spaces that safely retain dead trees and logs, whether standing or fallen, is not only a matter of preserving natural habitat but also of enriching our own lives by staying connected to the wilder parts of nature.

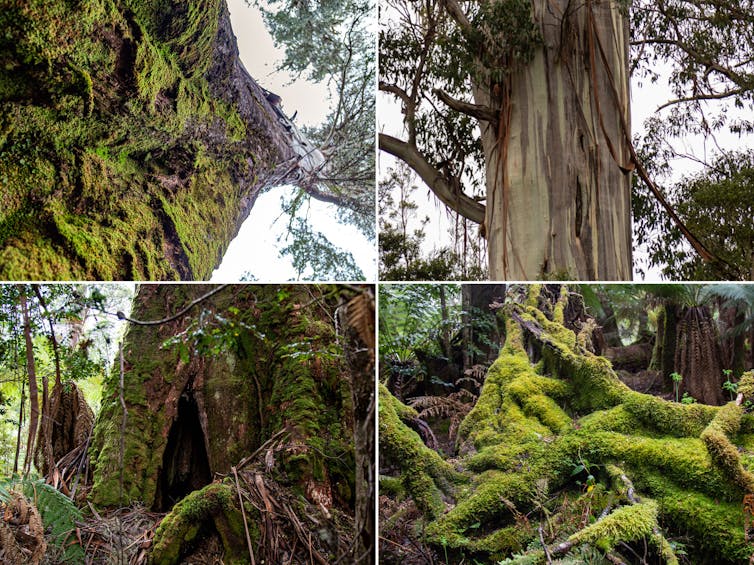

The Unique Value of Old Trees

A tree’s true ecological value increases with age. Mature trees develop features that simply don’t exist in younger ones, such as hollows, cracks, and peeling bark. More than 300 species of Australian native animals use these tree hollows for shelter, but they can take hundreds of years to form, making them an irreplaceable resource. The canopies of older trees are also more complex, featuring a higher density of the horizontal and dead branches that birds prefer for resting and nesting.

Designers and land managers must make it a priority to preserve old trees and integrate them into their planning processes. For homeowners, learning to appreciate the unique contributions of these ancient giants is key. By celebrating the wild, lush, and green character that old trees bring, we can create urban environments that are far from barren.

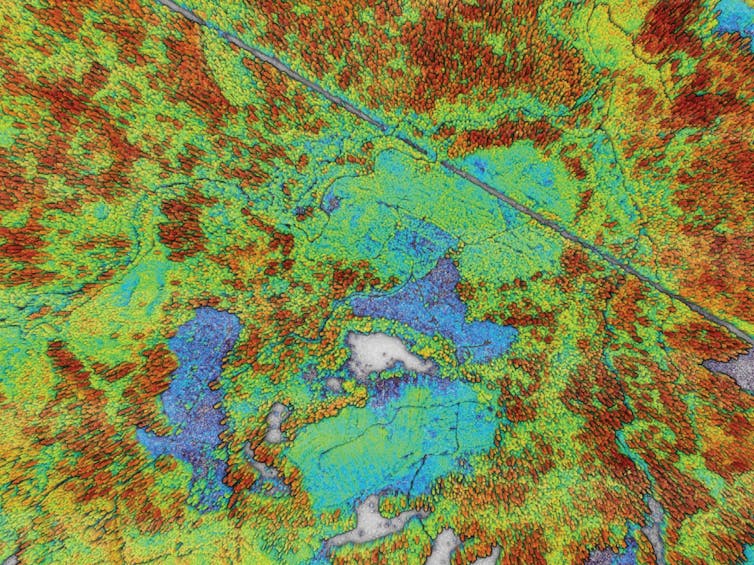

The Importance of Root Systems

Trees obtain water and nutrients through their roots, which adapt to maximize uptake even when resources are scarce. The soil surrounding a healthy root system also fosters beneficial microorganisms, helping to regulate the growth of nearby plants. Unfortunately, modern urban design often traps tree roots under hard, impermeable surfaces like concrete or bitumen, suffocating them and preventing them from performing their essential functions.

To counter this, we need to create permeable surfaces using materials like soil, gravel, bark chips, or perforated pavers. These allow fluids and gases to pass through, enabling roots to thrive. Urban spaces with healthy trees are demonstrably more biodiverse, resilient, cooler, and aesthetically pleasing, all thanks to the simple, yet profound, ingenuity of their root systems.

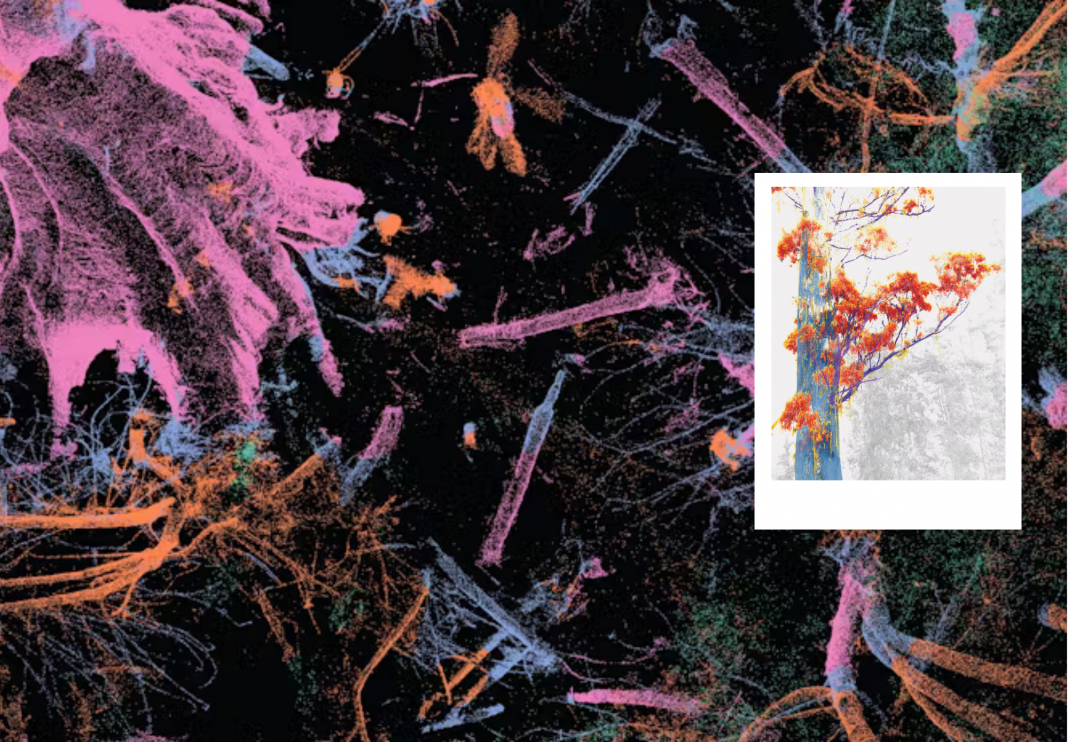

The Wisdom in Bark ‘Streamers’

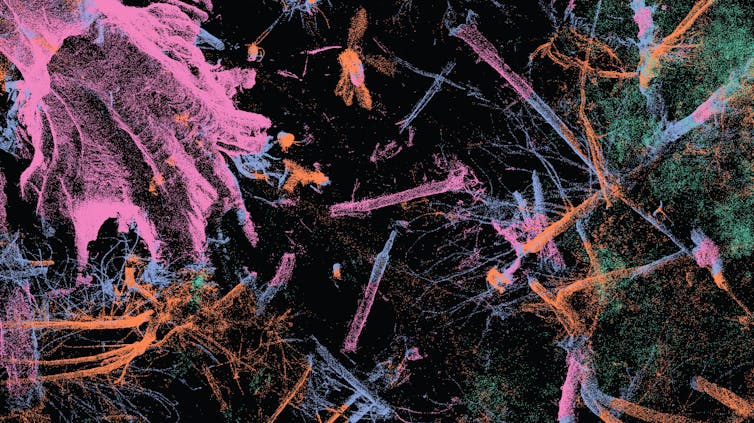

Those hanging strips of peeling bark, known as “streamers,” that adorn certain tree species are often overlooked, but they serve as microhabitats for insects like flightless tree crickets. The exact role of these features requires more research, but we know they contribute to the tree’s ecological value.

Designers can learn from this and apply the principle to urban maintenance, finding ways to retain these features while also managing risks like fire danger. The Deep Design Lab is even exploring how to use bark streamers as a blueprint to design artificial features that can enhance the ecological value of younger trees or add new homes for wildlife to human-made structures where natural trees cannot grow.

Embracing Natural Litter

The leaves, seeds, twigs, and branches that fall to the ground are not waste; they are a fundamental part of a tree’s genius. This organic litter enriches the soil, retains moisture, and provides habitat for fungi, insects, and other organisms. Yet, in urban areas, we often remove this material for aesthetic or safety reasons, unknowingly disrupting a critical ecological cycle. As a result, trees are deprived of nutrients and risk drying out, while the small plants and animals that depend on the litter are forced to leave.

Designers and the public should work together to find ways to retain organic litter using socially attractive strategies. This could include creating designated “wild zones” with clear signage explaining their purpose or modifying maintenance practices to preserve ecological benefits while still meeting public expectations. By taking our cues from these natural designs, we can create more sustainable and resilient environments for ourselves and all other living beings.