A newly restored portrait, unseen by the British public for a quarter of a century, is set to be the star attraction of a new exhibition at The King’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace. The painting, a vibrant depiction of a Roman model known only as Nanna, was the subject of a dramatic, almost scandalous acquisition by the future King Edward VII in 1859, when he was just a 17-year-old Prince of Wales. Created by the celebrated Victorian painter Frederic Leighton, the artwork—which Edward loved so dearly he kept it in his private rooms until his death in 1910—has been revealed in its original, sumptuous glory after painstaking conservation work stripped away a decades-old layer of yellowing varnish. The exhibition, entitled The Edwardians: Age of Elegance, is not merely a showcase of royal taste, but a deep dive into the formative years of a sovereign whose unconventional aesthetic choices began with a masterpiece he simply refused to live without.

The Prince’s Grand Tour and an Instant Obsession

The year was 1859, and the young Prince Albert Edward, or “Bertie,” the heir apparent to Queen Victoria, was engaged in the traditional, rigorously chaperoned Grand Tour of Italy. His travels through Rome were intended to be a strictly educational endeavor, carefully recorded in a journal for his father, Prince Albert. But even under the most watchful eyes, the prince’s emerging independence and personal tastes began to assert themselves. It was during a particularly busy day of artistic appreciation—his sixth studio visit, according to contemporary accounts—that the 17-year-old prince stepped into the working space of the English painter Frederic Leighton.

What followed was an instant, non-negotiable obsession. Leighton was already establishing his reputation, and his studio was a hub of expatriate artistic activity in Rome. Hanging among his works were multiple renderings of the same compelling subject: a beautiful Roman model known as Nanna. The young prince was immediately captivated by these depictions, recording his fascination in his journal: “I admired three beautiful portraits of a Roman woman, each representing the same person in a different attitude, & each giving quite a different interpretation of the same countenance.” It was a rare, raw expression of independent taste from a prince whose life was governed by royal duty. He admired all three, but he wanted only one for his own.

The Art of the Acquisition: Nanna’s Sudden Change of Owner

The Prince’s desire for the portrait of Nanna immediately created a delicate and awkward dilemma for Frederic Leighton. The chosen painting, a masterpiece of rich color and captivating emotion, had already been promised to and fully paid for by a dedicated collector, George de Monbrison. In a situation that could have devolved into a messy international incident, the Prince’s quiet but firm demand prevailed. According to the artist’s own discreet correspondence, Monbrison “has very kindly consented to give up his Nanna to the Prince.”

This forced change of ownership was a significant event, marking what is believed to be the Prince’s first independent acquisition of a painting. It was an exercise of royal will that gave a new dimension to his character, demonstrating both his assertive personality and his discerning, albeit unconventional, eye for art. The curator of the current exhibition suggests that this “whole story gives you a different perspective on the prince, he was probably not as uncouth as he is often portrayed,” positioning Edward VII as a figure of genuine aesthetic appreciation rather than a mere libertine. Meanwhile, a disappointed Monbrison was appeased by a generous offer from Leighton, who pledged to do what he would not under any other circumstance: paint a precise copy of the coveted work, which today hangs in the historic Leighton House in London.

Anna Risi: The Elusive Life of a Roman Muse

The sitter at the heart of this royal intrigue, the woman known as Nanna, possessed a life story as colorful and complex as the painting she inspired. Identified as Anna Risi, she was far from the aristocratic circles the prince was expected to frequent. She was originally married to a cobbler, but her striking beauty and expressive presence made her an immensely popular and sought-after model among the English and German artists working in Rome in the mid-19th century. Her professional life in the studios quickly led to a tempestuous personal life that defied the social norms of the era.

Anna Risi’s biography reads, in the words of a modern curator, like a plot that “really deserves an opera.” She left her cobbler husband to enter a relationship with a German artist, only to leave him later for an English man. When that relationship ended, either through her abandonment or his, she briefly returned to the German artist before, finally, vanishing completely from the historical record. The Prince of Wales was captivated by her image, but it is believed that he never actually met the model in person. This fact adds a fascinating layer to the artwork’s history: the future King of England was willing to use his influence to claim a painting of a woman he knew only by her painted image, a mysterious beauty who represented a free-spirited existence entirely foreign to his own rigidly structured life.

Rescuing the Masterpiece: A Conservation Triumph

For decades, the true magnificence of Leighton’s portrait of Nanna had been muted by time and unfortunate restoration choices. Before its current conservation, the painting had a “murky, hazy look,” largely due to a thick layer of waxy varnish applied in the 1970s. Over the subsequent half-century, this varnish had darkened, attracted dirt, and, most damagingly, blurred the nuances of the artist’s hand, effectively obscuring the vibrant texture and subtle details of the Pre-Raphaelite master’s work.

Conservator Nicola Christie undertook the delicate process of conservation, a triumph of patience and technical skill that resulted in a remarkable artistic revelation. By removing the degraded varnish, the original rich, deep colors and the “swirling brush strokes” were rescued. Details that had been almost invisible suddenly emerged, including the presence of fruit and delicate peacock feathers in the background, which adds symbolic depth to the composition. Furthermore, the true subtlety of Leighton’s palette was restored, revealing hidden tones of blue and purple in the model’s gleaming dark hair, and allowing the shimmering pearls around her neck to reflect the light as they did when painted. The conservator noted the portrait’s powerful quality, describing the original as having a “real energy in the brush work,” especially when contrasted with the artist’s own meticulously executed copy.

From Student Rooms to the King’s Gallery

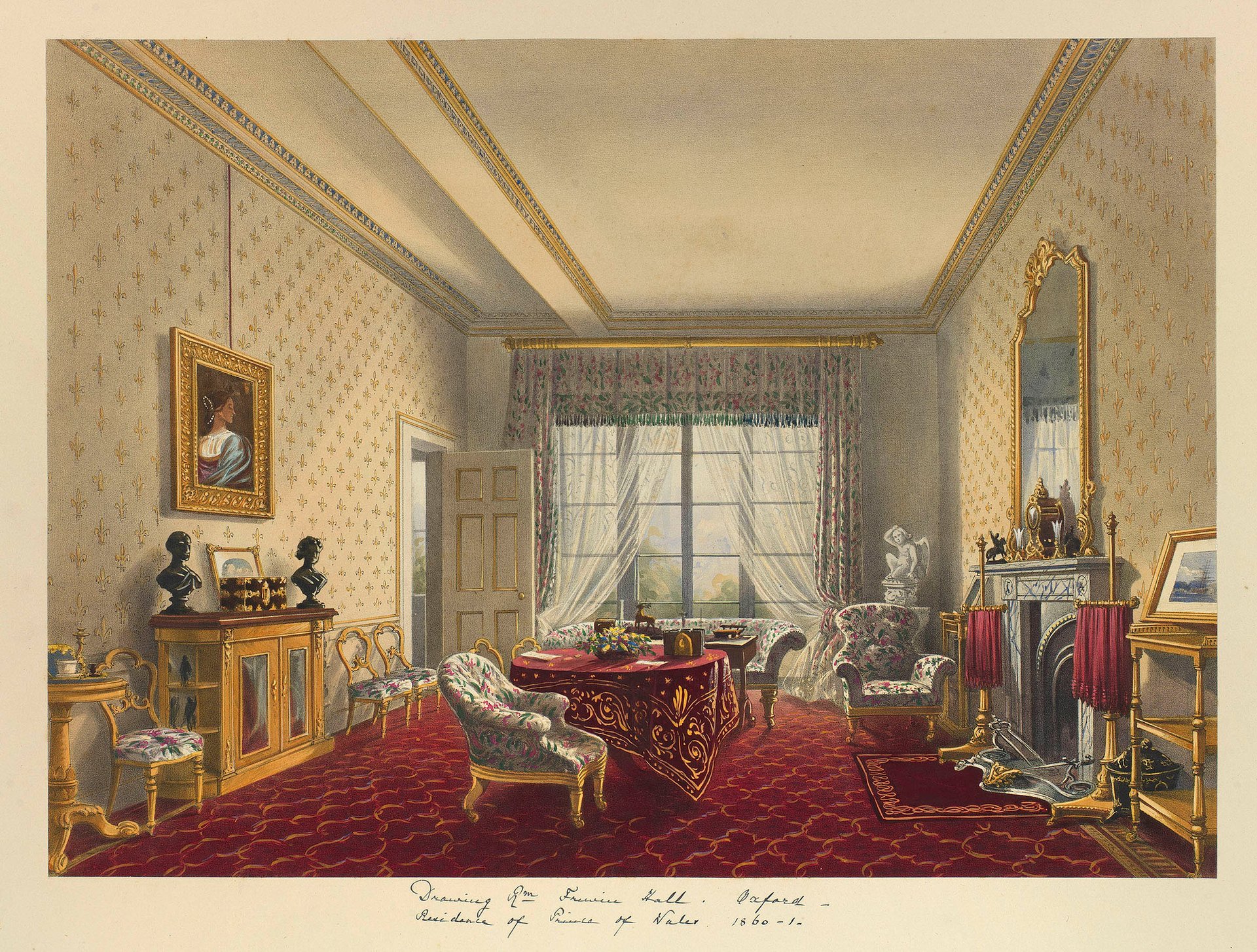

The portrait of Nanna was not merely a trophy purchase; it became a fixed point in the private life of King Edward VII, a constant companion that symbolized his early aesthetic independence. The evidence of the painting’s importance is well-documented within the Royal Collection. Soon after its dramatic acquisition in 1859, the portrait, often hanging next to Bianca—a meeker view of a different model—took pride of place on the walls of the prince’s sumptuous student rooms at Frewin Hall, Oxford.

As Edward moved through the decades and ascended through his royal titles, Nanna followed. The painting moved with him to Marlborough House in London, and most tellingly, it was documented hanging in his personal dressing room in Buckingham Palace in 1910, the year of his death, positioned among an impressive array of walking sticks and Homburg hats. The portrait, therefore, offers a silent narrative of the King’s entire adult life, confirming his own early judgment of quality and beauty. Its inclusion in The Edwardians: Age of Elegance at The King’s Gallery provides not only a spectacular artistic centerpiece, but a profound, personal insight into the hidden tastes and independent character of the sovereign who ushered in an era of luxury and sophistication.